Brent Marchant

7

|

Aug 27, 2025

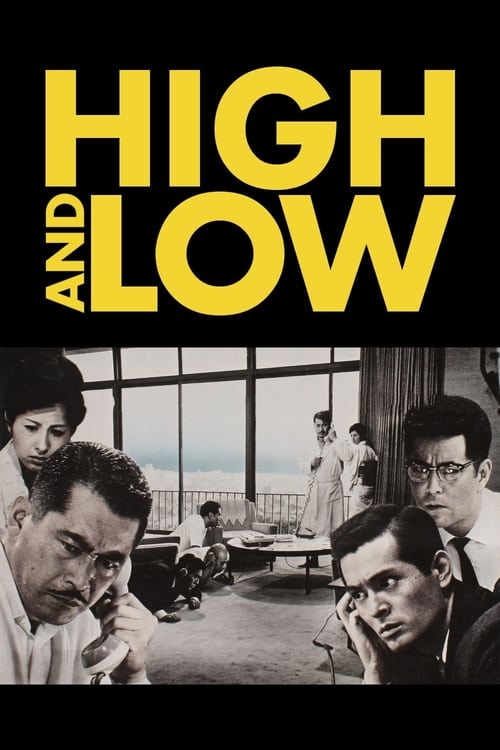

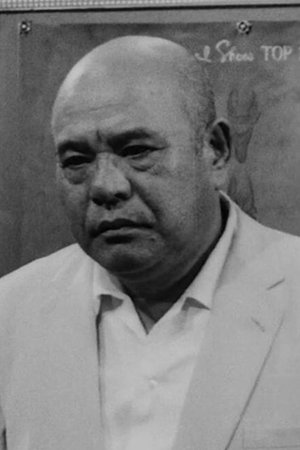

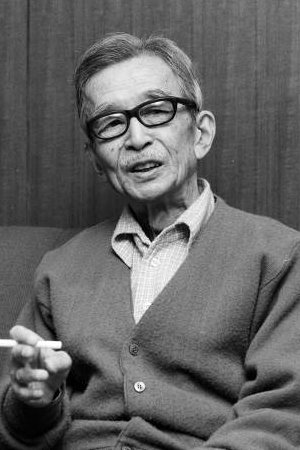

I’m always amazed at how a single film can be fundamentally characterized in multiple ways, but that’s understandable when the picture combines an array of diverse elements, each of which has a validity all its own that can subsequently lead to different overarching interpretations. Such is the case with this 1963 film classic from famed Japanese auteur Akira Kurosawa, which provides the cinematic inspiration behind filmmaker Spike Lee’s current reimagination, “Highest 2 Lowest,” now playing theatrically. Like the current iteration, “High and Low” follows the story of a wealthy businessman, Kingo Gondô (Toshirô Mifune), who’s looking to take control of the shoe manufacturing company for which he works, a plan that requires him to leverage his entire personal fortune to make it possible. But, just as he’s about to close the deal, he’s distracted by the alleged kidnapping of his young son (Toshio Egi), a crime for which the perpetrator demands a ransom equal in value to the funds needed to cover the pending transaction. However, not long after hearing about the kidnapping, Gondô learns that the culprit has nabbed the wrong child, erroneously taking the son (Masahiko Shimazu) of his chauffeur (Yutaka Sada). But Gondô is not off the hook: the kidnapper still demands payment of the ransom, even though the crime doesn’t involve his son. This leaves Gondô with a huge moral dilemma: does he use the money to close his business deal or to pay the ransom of his employee’s child? As Gondô grapples with this decision, an intense police investigation ensues to discover the kidnapper’s identity and to figure out a way to retrieve both the victim and the ransom money. Unlike the current film, though, Kurosawa’s version focuses less on the particulars driving this scenario and more intently on the ethical questions that the protagonist is left to wrestle with, issues ultimately symbolic of the divisive class and economic disparities in Japanese society. Indeed, while the picture provides viewers with its share of intense thriller moments, in many regards it’s really more of a morality play, not only where Gondô is concerned, but also in its exploration of the inherent chasms between rich and poor, privileged and impoverished, and control and servitude. (This attribute, in turn, helps to shed light on the nature of the film’s character and the relevance of its original Japanese title, “Tengoku to jigoku,” which translates to “Heaven and Hell,” in my opinion a more fitting appellation that probably should have been retained when renamed in English.) The foregoing aspects of the picture thus distinguish this predecessor work from the current release, even though the exact nature of the nexus between kidnapper and target is not developed as fully here as I believe it should have been (one of the few ways in which the present offering modestly improves upon the original). In addition, there are times in the opening act, as well as in the run-up to the film’s conclusion, when the storytelling could have been a little brisker (the slower pacing style of the period in which the picture was made notwithstanding). Still, this offering’s social and cultural themes are nevertheless intriguing, and their place here has a tendency to grow on audiences as the picture progresses. And those thematic aspects, when combined with the contrast of the narrative’s riveting criminal investigation, make for an intriguing mix, one that undoubtedly accounts for the differing perspectives that this release often evokes among viewers. While “High and Low” may not be Kurosawa’s best work when compared with such pictures as “Rashômon” (1950) and “Ikiru” (1952), it stands out as one of the filmmaker’s most thoughtful and engaging works, one that probes the heaven and hell that reside here on Earth, both individually and at their points of intersection, and how the lines between them can become all too easily blurred, a caution to us all.