AshenArcanist

9

|

Apr 07, 2025

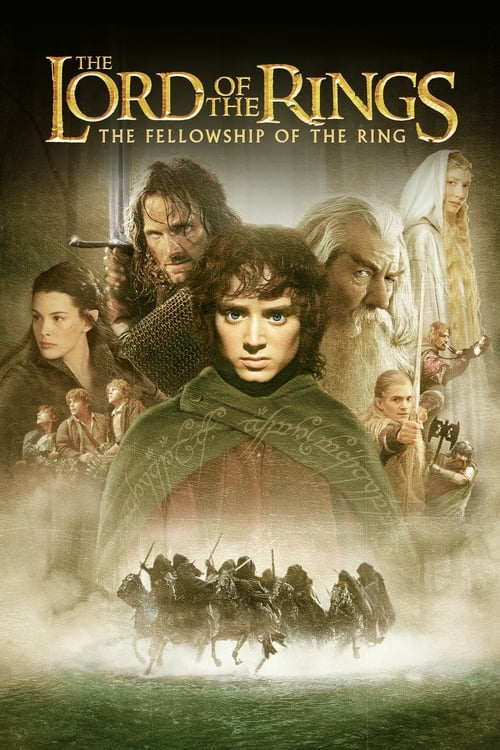

One Trilogy to rule them all. Peter Jackson’s The Fellowship of the Ring, the start of this epic journey, remains unmatched in its reverence for Tolkien’s work – not merely as an epic tale, but as a moral and mythological construct with its own internal gravity. Unlike many contemporary fantasy productions, which often treat Tolkien’s world as a loose template to be re-skinned, Jackson’s film operates as a careful translation, not a reinvention. Every creative decision, from script to score to set design, reflects an understanding that Middle-earth is not a playground, but a legendarium – a world with its own laws, languages, and deeply rooted cosmology. It is this sense of literary responsibility that makes Fellowship not just a good adaptation, but a great one.

Too many modern shows, even those cloaked in Tolkien’s vocabulary, feel less like adaptations and more like speculative reinterpretations – injecting modern anxieties and tropes into a narrative that was already rich in timeless concerns. Where those newer productions often flatten the moral contours of the story into grey ambiguity or impulsive spectacle, Jackson’s Fellowship preserves the text’s theological seriousness and philosophical clarity. It understands, crucially, that Tolkien was not writing about swords and sorcery, but about humility, sacrifice, and the perilous allure of domination. The Ring is not a mere object of power – it is a spiritual test – and the film never lets us forget it.

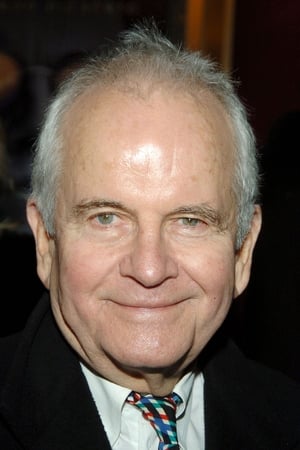

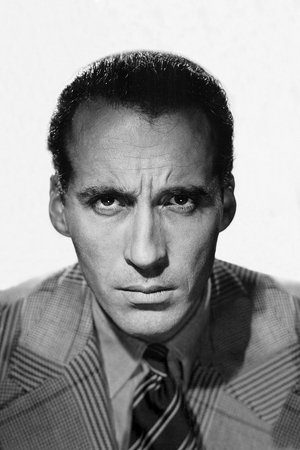

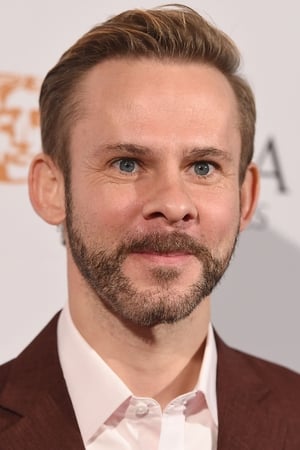

The performances reflect this deeper understanding. Ian McKellen’s Gandalf is not a stock wizard, but a being of deep time, burdened by knowledge and reluctant authority. Elijah Wood’s Frodo captures the very soul of Tolkien’s hobbit – a creature of small stature and immense will, shouldering a task no one would envy. Sean Astin’s Samwise is played not for comic relief, but as a paragon of unsung virtue: loyalty without ambition, courage without ego. Viggo Mortensen’s Aragorn is a man wrestling with history, shaped by the burden of lineage, not the thrill of it. These portrayals are not just emotionally effective; they are textually faithful.

Cate Blanchett’s Galadriel deserves special mention. Her portrayal embodies the strange, luminous power of the Elves as Tolkien wrote them – otherworldly and terrible in equal measure. Her temptation scene is delivered with haunting restraint, the grandeur of her voice a vessel for ancient sorrow and quiet wisdom. This Galadriel is not a warrior queen in the modern sense, but a bearer of deep time, whose greatness lies in her refusal to grasp at power. It is a performance that understands the Elvish condition: to be fading, beautiful, and bound to a world no longer theirs. Blanchett’s screen time is brief, but the echo of her presence lingers – like Elven light in dark places.

Jackson’s adaptation respects Tolkien’s languages and mythic structures with near-obsessive care. Elvish is not set dressing; it is spoken with phonetic integrity, tied to cultures that feel ancient and real. The geography, costumes, architecture – each bears the mark of deep lore, not just visual flair. Howard Shore’s score, informed by the same gravitas, does not accompany the film so much as inhabit it. His themes are not just musical motifs but narrative threads, echoing the rise and fall of kingdoms and the quiet dignity of small acts of heroism.

What distinguishes The Fellowship of the Ring is that it treats Tolkien’s world as something already complete – something to be entered humbly, not reshaped. In doing so, it achieves a rare artistic feat: it becomes an extension of the text, not a commentary on it. While newer works may borrow Tolkien’s lexicon and aesthetics, Jackson’s film believes in his world. It does not merely entertain; it partakes in a mythology. That belief, that reverence, is what endures.